Medical Writing in Pediatrics

A short introduction to pediatric drug development for medical writers

“Neonates are not just small children and children are not just small adults.”

Challenges in pediatric drug development

Developing drugs for the pediatric population presents with additional challenges beyond the already intricate process of adult drug development. These challenges come as a consequence to the numerous developmental changes that neonates and children undergo throughout their first months and years of life, many of which can influence the disposition and (adverse) effects of therapeutics.

These include changes in:

- the metabolic capacity of the liver (eg, availability of CYP450 and UGT enzymes),

- distribution sites (eg, proportion body water/fat),

- gastrointestinal function (eg, stomach acid production and the intestinal surface area),

- renal function (eg, the glomerular filtration rate),

- integumentary development (eg, the skin surface area),

- and age-related maturation determining pharmacodynamics (eg, availability of receptors and ligands).

Considering all of these factors when determining the preclinical rationale, translational relevance, formulation, clinical endpoints, and study design for new drug candidates intended for the pediatric market, may prove to be a difficult task.

Regulatory framework

In the past, clinical studies in children were very limited; not only due to challenges in study design, but also because of ethical constraints. In general, children were exposed to clinical studies as little as possible to protect them from any possible harms, as they are a vulnerable population who cannot provide an informed consent of their own. Furthermore, the historical lack of specific regulations for pediatric drug development hindered the design and execution of validated clinical studies in the pediatric population, leading to widespread off-label and unlicensed drug use, often based on empirical weight-based dosing. As a result, administration of drugs in children was often ineffective and undeniably unsafe, with efficacy and safety information specific to the pediatric population remaining undefined.

To address this, specific laws for pediatric drug development encouraging companies to develop effective medicines for children were introduced — first in the US in 1997 and later in the EU in 2007. These regulations mandate pharmaceutical companies to consider how their medicines will affect children early in the drug development process, requiring them to carefully assess the scientific necessity and benefit-risk ratio of any pediatric clinical study. Pediatric studies should be planned from the beginning rather than as an afterthought. The regulations also require the submission of a Pediatric Study Plan (PSP) in the US or a Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP) in the EU to the respective competent authorities, such as FDA and EMA, for approval prior to initiating any clinical studies in children.

Regulatory medical writing

The process of designing and gaining approval for clinical studies in children requires careful preparation, including comprehensive documentation, where medical writers play a crucial role. The PSP and PIP aim to outline and plan the necessary pediatric studies. These documents should be submitted by the end of the Phase I trials, before the proof-of-concept stage. During their preparation, scientific advice can be obtained from the competent authorities, with negotiations following submission.

The PSP or PIP should cover

- information on the indication, justification for the selected pediatric subset(s), and an overview of existing quality, nonclinical, and clinical data,

- planned and/or ongoing measures in formulation development,

- planned and/or ongoing nonclinical studies,

- the proposed strategy for pediatric clinical studies (eg, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies and safety and efficacy studies),

- any other studies (eg, modeling, simulation, and extrapolation studies),

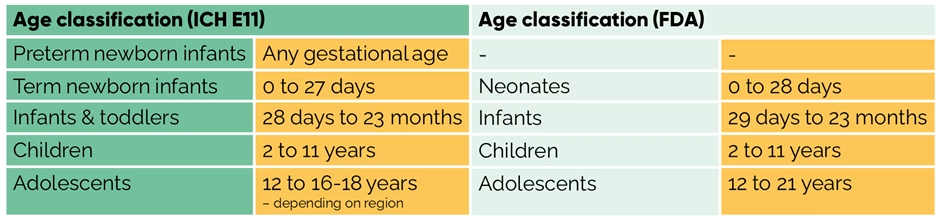

- and all age groups as defined by ICH E11 (guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products in the pediatric population) or the FDA (see table below).

In the end, the results of the studies agreed in the PSP/PIP determine the decision on granting marketing authorization of a medicine to be approved for children.

All other regulatory documents to be developed throughout the pediatric drug life cycle must also reflect and address the specific needs and challenges of pediatric drug development. One example is the informed consent form. Currently, there is no global consensus on the informed consent process for pediatric clinical studies. In general, parents are required to sign the informed consent form, and once a child reaches a certain age, they may sign an assent form. However, in some countries, adolescents are allowed to sign an informed consent themselves, and the age ranges for assent vary between countries. The European Network of Paediatric Research at the European Medicines Agency (Enpr EMA) provides the following toolkit on consent and assent: https://eapaediatrics.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2-ENPR-EMA-Consent-assent-Toolkit.pdf.

Are you planning to conduct pediatric studies and looking to outsource medical writing for any key regulatory documents? Emtex Life Science medical writers can play a crucial role in the document development process. They can guide the team in providing the necessary information, draft documents, or write specific sections, ensuring that all requirements and guidelines for pediatric clinical studies are met.